Building a DIY ESP Temperature Logger to Find Out

Modern access points are no longer just radios.

They’re basically small servers with antennas.

- Multi-core CPUs.

- Three radios.

- 320 MHz channels.

- Multi-Gig uplinks.

- Up to 60 watts PoE.

Which raises a very simple but very practical question:

How hot do they get?

And more importantly:

What happens when you put one inside a sealed enclosure?

The Problem

We are rolling out new Cisco C9176 Wi-Fi 6E/7 access points.

These devices must be installed inside existing Thuba EX enclosures that were originally designed for older, less power-hungry hardware.

More power means more heat.

And heat inside a closed plastic box is rarely a good thing.

Higher temperatures can reduce:

- lifetime

- stability

- RF performance

- component reliability

Instead of guessing or relying on datasheets, we decided to measure it properly.

The Goal

We wanted real numbers.

Specifically:

- temperature inside the enclosure

- behaviour at 30 W vs 60 W PoE

- idle vs heavy traffic

- long-term stability

No cloud.

No complex lab setup.

Just a small autonomous logger that runs for days.

Building the Temperature Logger

Rather than buying a commercial system, we built one.

Because honestly — this is the perfect excuse to play with microcontrollers.

The idea:

A tiny ESP that:

- measures temperature

- timestamps values

- logs to flash

- hosts a small web interface

All self-contained.

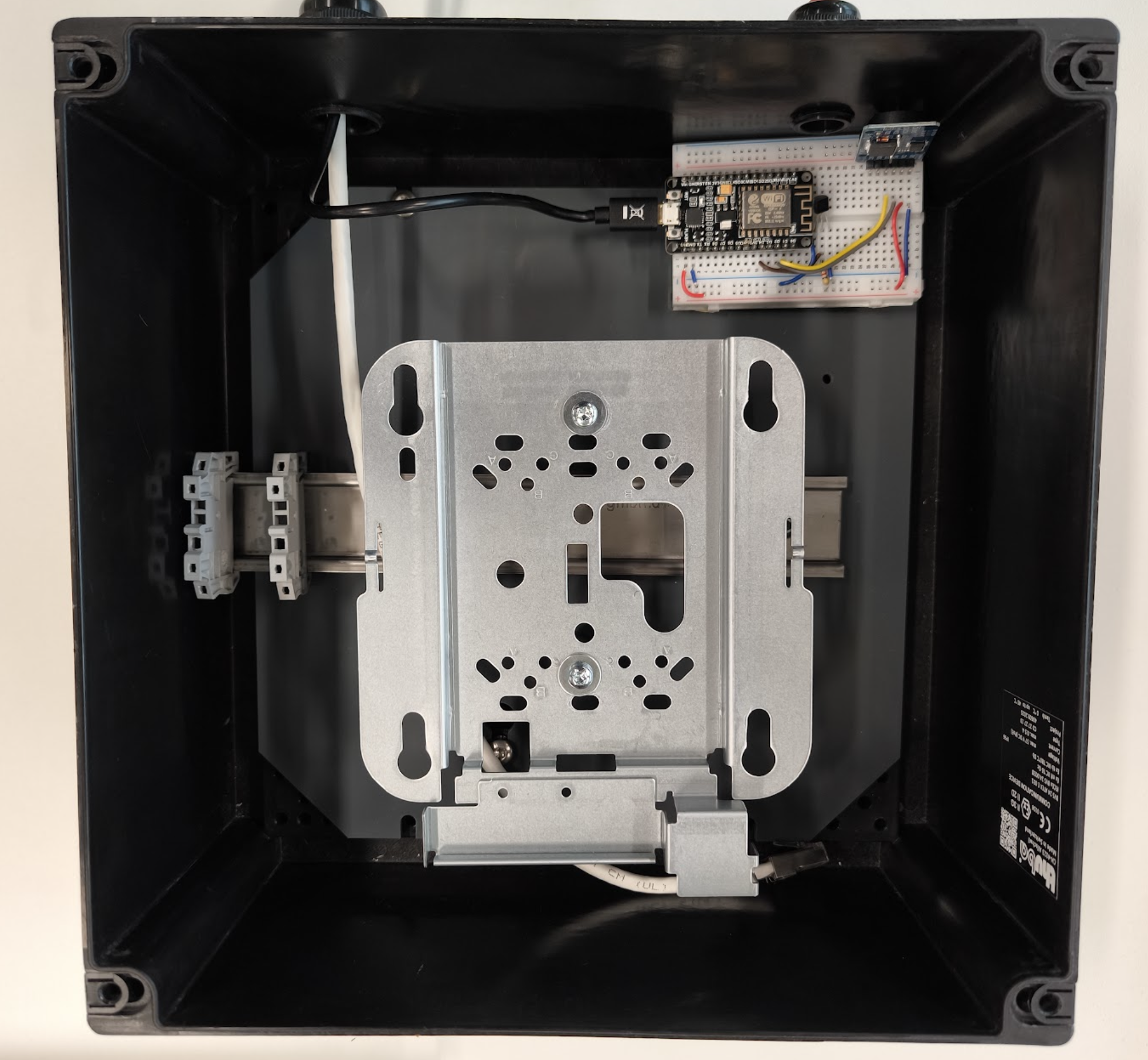

Hardware

Components used:

- ESP8266 (NodeMCU)

- DS18B20 temperature sensor (TO-92 chip)

- DS3231 RTC (real time clock)

- 4.7 kΩ pull-up resistor

- breadboard + USB power

Cheap, simple, reliable.

This is the complete logger. No fancy PCB. Just pure lab energy.

Wiring

The sensor uses 1-Wire.

The clock uses I²C.

Three wires and a resistor. Done.

Software

The firmware is intentionally minimal.

Every 5 seconds it:

-

reads temperature

-

gets timestamp from RTC

-

appends CSV line to flash

Example:

Simple formats are beautiful.

Excel loves them. Python loves them. Everything loves them.

You can Download the Code from my Github page:

https://github.com/samuelheinrich/ESP8266_Temperatursensor

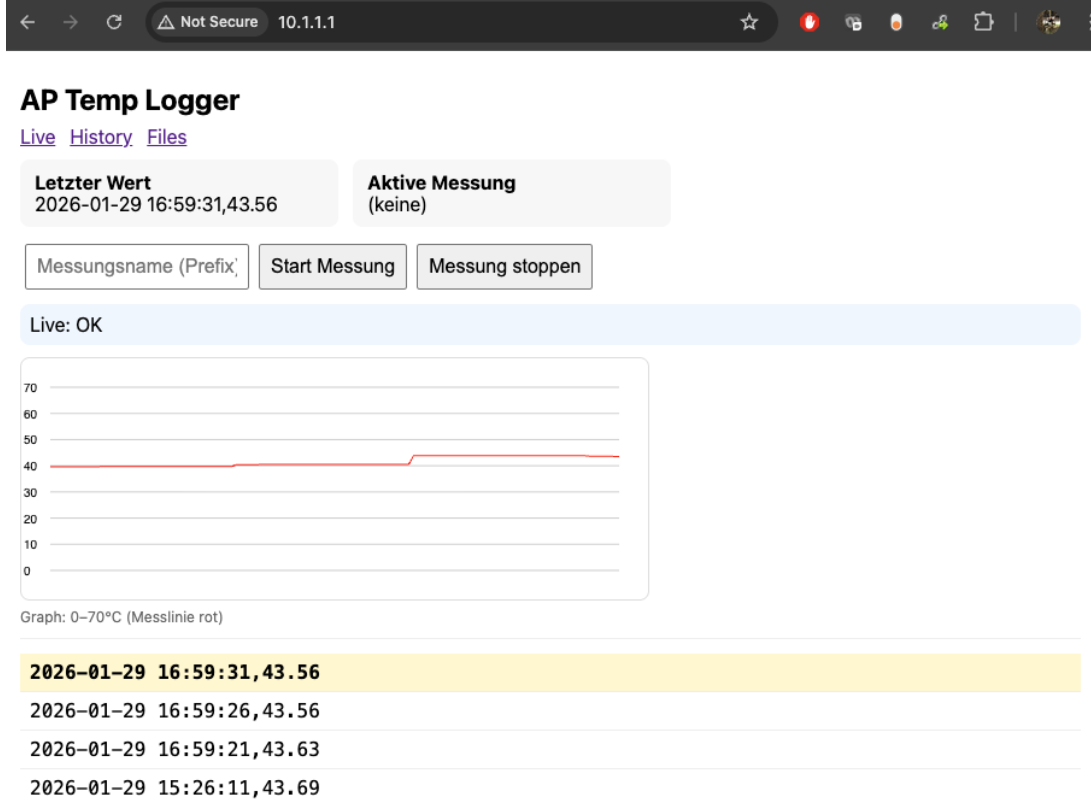

Built-in Web Interface

The ESP also creates its own Wi-Fi access point:

No router needed.

Open browser → done.

Features:

- live values

- history

- real-time graphs

- start/stop measurement

- CSV download

- file delete

It’s basically a tiny self-hosted logging appliance.

Installing It Inside the Enclosure

The DS18B20 chip is placed freely in the air space of the housing.

Not glued to metal.

Not touching the AP.

We wanted ambient internal air temperature, not hotspot readings.

The logger board is mounted inside the enclosure and powered via USB.

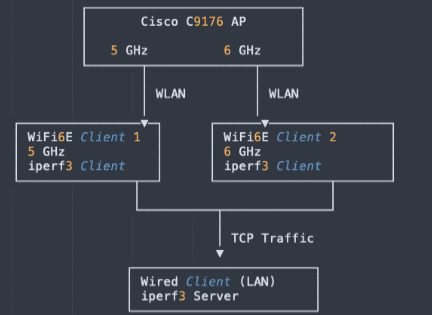

Generating Load

Idle temperatures are boring.

We needed worst case.

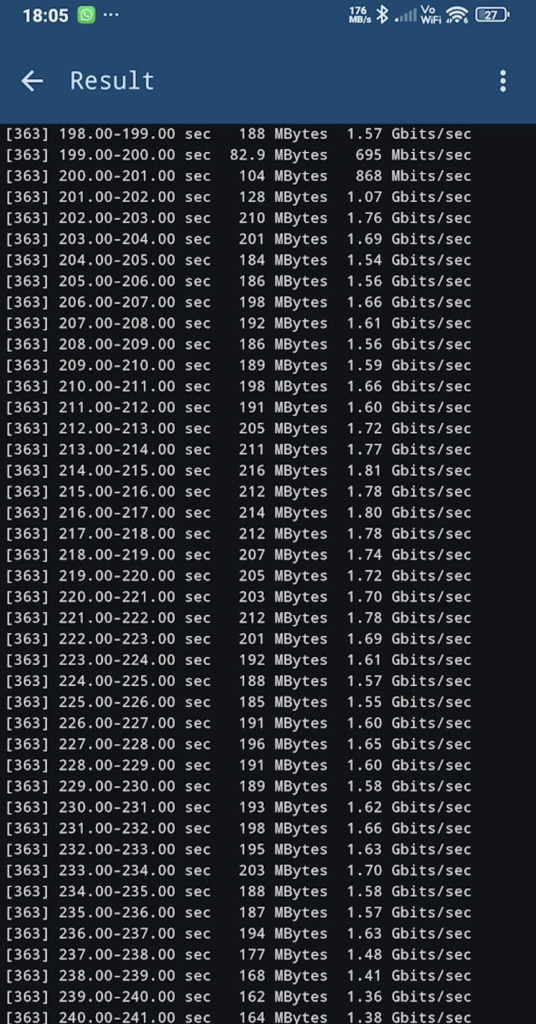

Traffic generation was done with iperf3 (TCP).

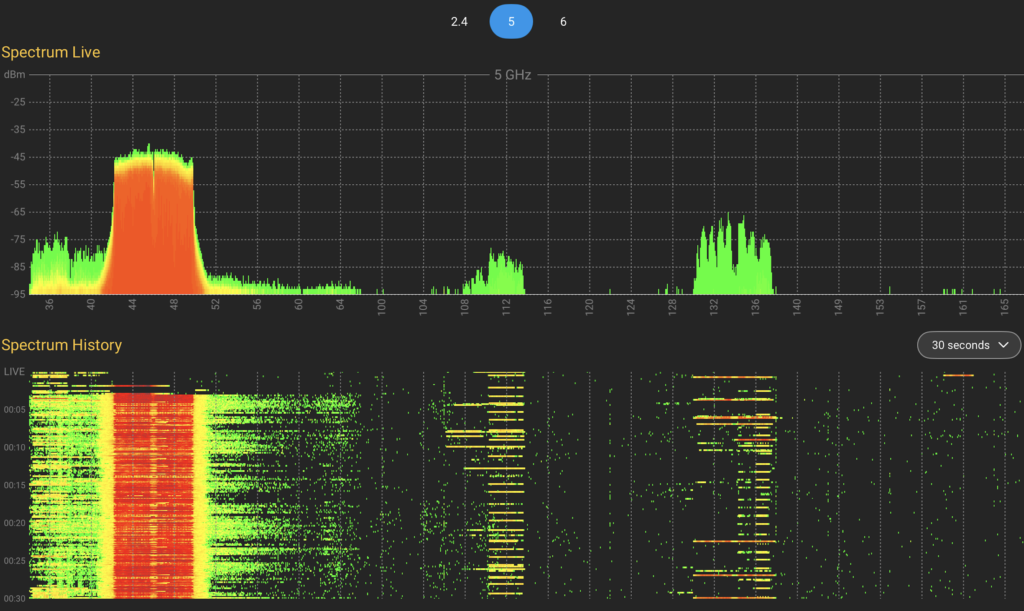

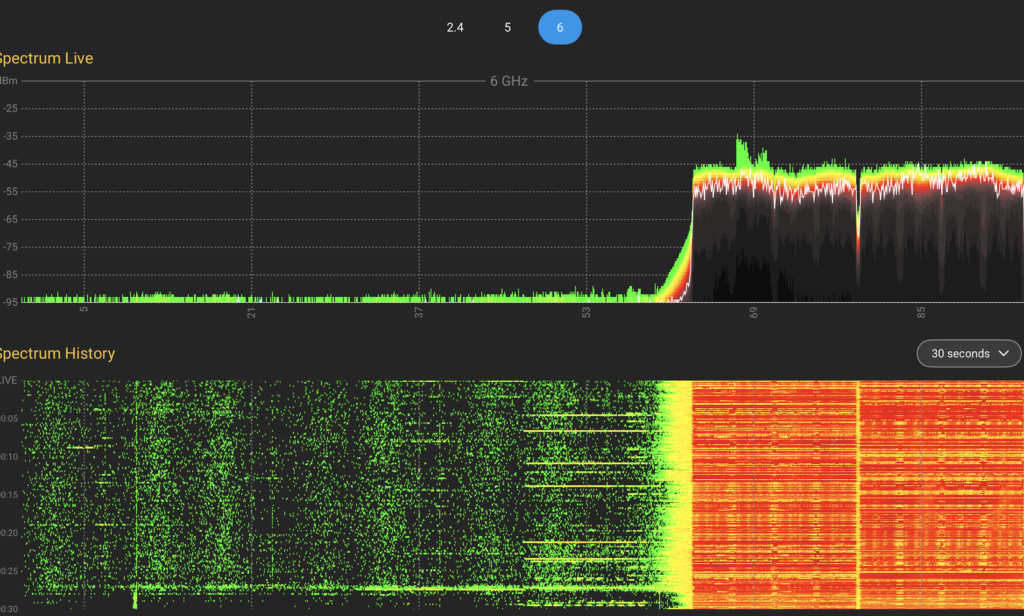

Two Wi-Fi 6E clients streamed traffic to a wired server:

Single-band only per test to isolate each radio.

WIFI Client 1 -> 5GHz 80Mhz 2SS

WIFI Client 2 -> 6GHz 160MHz 2SS

Let’s go!!!

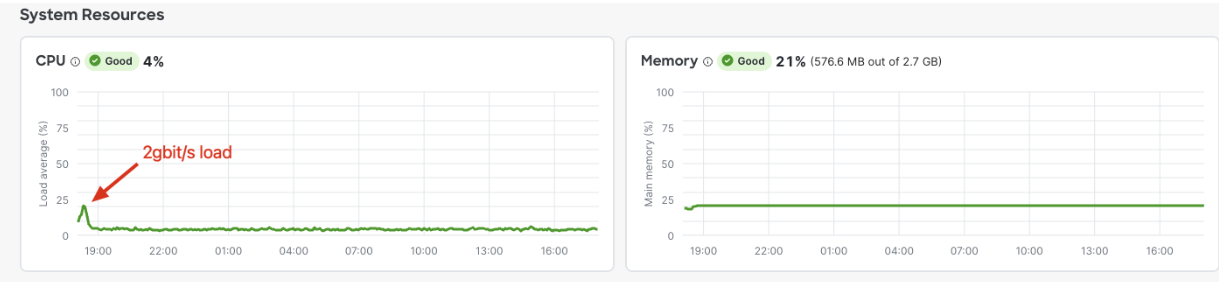

CPU Impact during Traffic Load

To confirm real RF activity, we also checked spectrum usage.

Test Plan

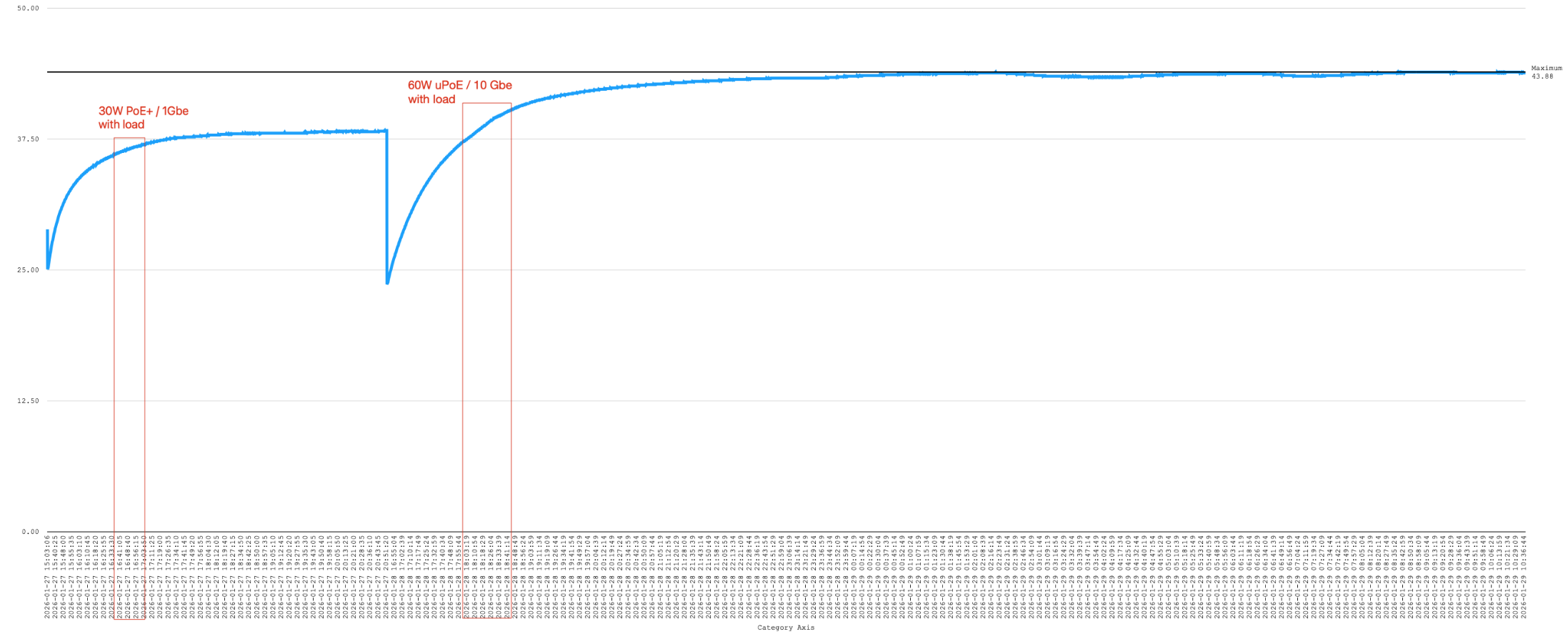

To avoid too many variables, we kept it simple.

| PoE Mode | Radio Power | Traffic |

|---|---|---|

| 30 W | full | idle |

| 30 W | full | load |

| 60 W | full | idle |

| 60 W | full | load |

Lower power tests were skipped intentionally.

We focused on realistic worst-case behaviour.

Results

The temperature curves all showed the same characteristic behaviour:

• fast warm-up after power-on

• exponential rise

• stable plateau

Classic thermodynamics at work.

Switching from idle → load produced visible temperature steps.

Switching from 30 W → 60 W increased the plateau further.

Exactly what physics predicts.

Maximum observed temperature

Across all tests:

43.86 °C

That was the highest value recorded.

No spikes.

No instability.

No runaway heating.

Interpretation

Even with:

• full radio power

• heavy TCP load

• 60 W PoE

…the enclosure stayed comfortably within Cisco’s specified operating range (0–50 °C).

So the box behaves more like a warm cupboard than an oven.

Good news.

What Could Be Different in Production?

Real life is always messier than lab tests.

Temperatures may increase with:

• higher ambient temperature

• direct sunlight

• more clients

• higher CPU load (FlexConnect, QoS, encryption)

• constant peak traffic

• poor airflow

• PoE inefficiencies

So treat this as baseline guidance, not a guarantee.

Conclusion

A €10 microcontroller and a temperature sensor answered a question that could otherwise cause weeks of speculation.

Instead of guessing:

We measured.

Instead of theory:

We logged data.

And the result is reassuring:

The Cisco 9176 runs safely inside the existing enclosure — even under worst-case load.

Sometimes the best engineering tool isn’t a complex monitoring system.

Sometimes it’s just:

a tiny board,

a resistor,

and curiosity.

Download als PDF File

Download als PDF File